Steaking a Claim: Is Haem Iron the Hidden Culprit in Diabetes?

Let’s evaluate these New Data from Nature Metabolism, out last week.

I’m updating this Newsletter to highlight a 12 minute video that includes my thoughts on 2 recent publications on the link between Red Meat and Diabetes. If you want to “two birds one stone” it, check out this video.

Original Newsletter

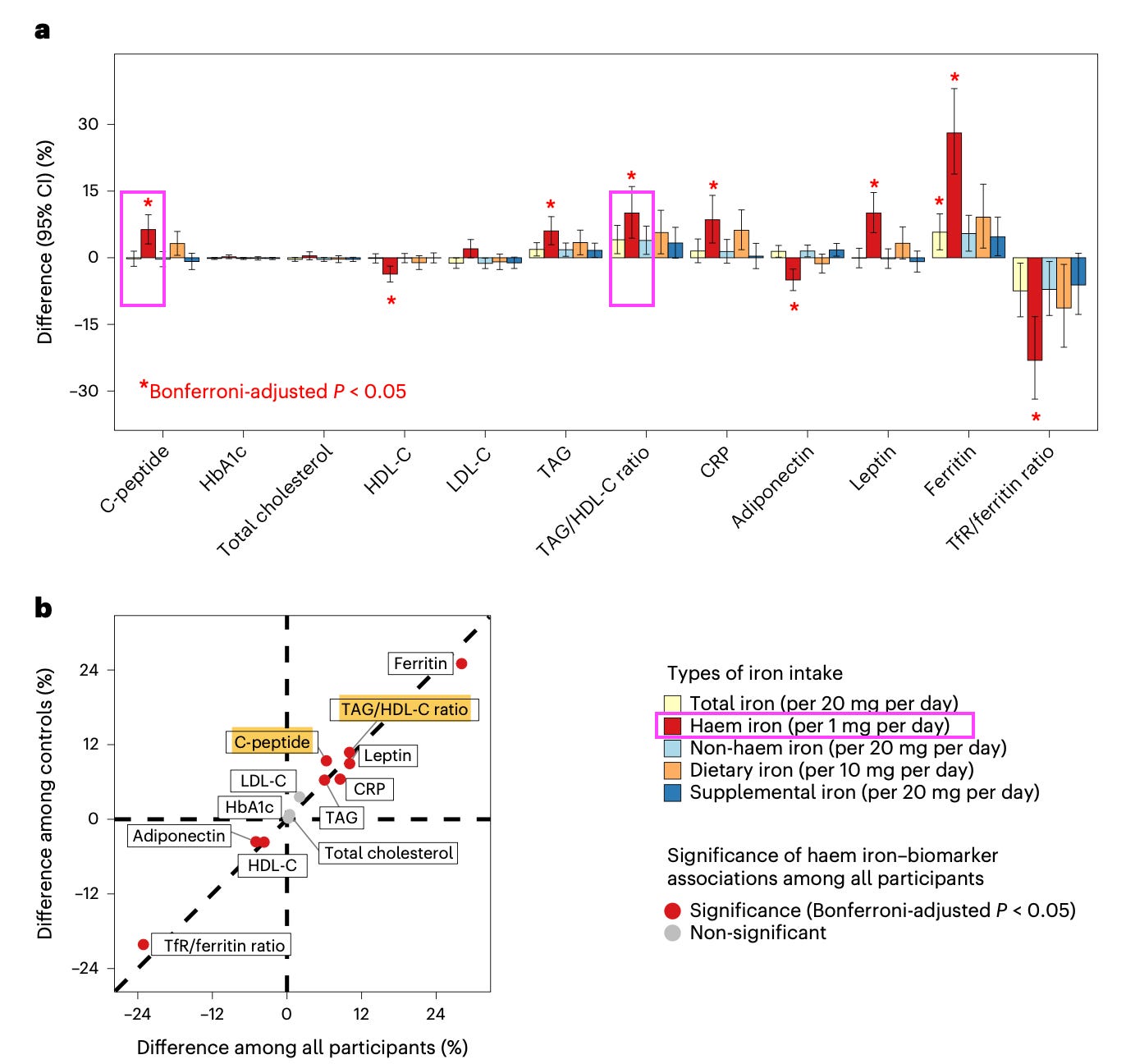

A new study in Nature Metabolism, published last week, asserts “Here we show that haem iron intake but not non-haem iron is associated with a higher T2D risk.”

It concludes, “These findings have important public health implications in shaping guidelines to prevent diabetes by limiting the daily consumption of foods rich in haem iron, particularly red meat.”

Methods

The primary analysis was conducted on 204,615 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS2) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS).

The researchers quantified associations between total, haem, and non-haem iron and T2D risk & between iron intake and established metabolic biomarkers.

Basic Confounders

Of note, participants with greater haem iron intake were generally less physically active, more likely to smoke and had higher BMI.

Furthermore, haem iron intake was positively correlated with a Western style-diet, which includes more “sweets and desserts, french fries, and refined grains,” here quoting from reference 31, where Western diet score is characterized.

To their credit, the authors of the current paper note that the association between dietary patterns and T2D risk could “also be partly due to… high added sugar in the Western diet…”

Metabolomics

Among the most prominent metabolomic findings were that C-peptide (a marker of insulin release), and TG/HDL-C ratio were higher with more haem iron intake.

Given this correlation, and the fact that whatever underlying metabolic dysfunction contributes to T2D risk also likely manifests in worse markers of metabolic health (e.g. high C-peptide/insulin/insulin resistance, high TG and low HDL-C), I’d suggest that if one’s metabolic markers are ‘optimized’ these data have little relevance on the individual level.

The beautiful thing about metabolic health science is that the “proof is in the pudding” (i.e. the markers, both metabolomic and functional).

So, if a study says, “X-containing food is associated with Y ‘bad’ markers and Z ‘bad’ outcome,” but you eat a lot of X-containing food, and your markers are excellent… well… the conclusion should be obvious.

Of course, this cuts both ways, and I’d never criticize someone for abstaining from red meat, or eggs, or any food if they are themselves doing well. To each their own. Humans are heterogenous.

Biological Plausibility

For these associational studies, I always go looking for biological plausibility arguments. The steel man case made in the discussion was “haem iron, acting as a potent pro-oxidant, could exacerbate the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, promoting oxidative damage and inflammation—key factors in the diabetes pathophysiology” and that “[Our data] suggest the involvement of insulin resistance [and] inflammation.”

I don’t discount this entirely and, in general, have an open mind to the possibility that high levels of haem iron intake, particularly in a Western diet context, could increase risk of T2D by promoting oxidative stress and inflammation. That’s certainly possible.

However, given the humble size of the association in this study (OR 1.26) and significant confounders noted above, I’m inclined to be less concerned about the steak than I am about the “sweets and desserts, french fries, and refined grains” and smoking.

Concluding Thoughts

These associational data are interesting and fine for hypothesis generation.

However, there are confounders and “statical adjustments and modeling” may not be sufficient to account for these entirely.

One can choose to limit haem iron containing foods if they so choose. However, high sugar intake, obesity, a Western-style diet rich in refined carbohydrates, and a sedentary lifestyle are all much larger risk factors than eating steak. I hope that’s obvious.

Note: *This is a different style of Newsletter. It constitutes a quick digest of a paper that I was asked by a colleague to evaluate last night. Effectively, I’m rewording what I’d put in an email reply to this colleague and disseminating it via the Newsletter to you. Let me know if you like this format or if you feel it ‘dilutes’ my regular content. Balance of quality and quantity is important.*

I like this quick, understandable format. Simon Hill X’d about this study and I immediately thought, “I wish Nick would give us his take”. Thank you for making my wish come true.

Thanks Nick! Always quick to respond and never disappoint. Your're the man (metabolic man)!

Jim & Greenie