How Stress Destroys the Microbiome. And What To Do About It.

We will review new data published in Cell on how stress directly impacts the microbiome and gut health, and provide practical takeaways.

The questions of the day are:

How does psychological stress impact gut health?

How can we use new science, new knowledge to improve our gut health and our mental health?

Without further ado… Let’s roll!

New Paper

The paper in question I want to cover in this brief Newsletter was just published in Cell and is entitled “Stress-sensitive neural circuits change the gut microbiome via duodenal glands.” Here’s the graphical abstract.

At a high level:

The researchers discover a pathway whereby activity in a brain region associated with stress and emotions, the amygdala, controls the Vagus nerve that connects the brain to the gut.

In so doing, the brain can “toggle” the activity of glands in the intestines called Brunner’s glands that make mucin that feeds the microbiome, which in turn influences GI symptoms and gut health.

Adding some details:

The leading gut bug in our story is Lactobacillus. There are many different species in the genus Lactobacillus, but for the sake of simplicity consider the Lactobacillus “good guy gut bugs” – they’re a common probiotic and also the primary genus found in many considered healthy fermented foods, like yogurts, sauerkraut, kimchi etc.

Shown here, the researchers found that “stimulation” of mucin-secreting Brunner’s Gland in mice provided nourishment to Lactobacillus and promoted growth (large pink bar; second from the left).

However, surgical removal of Brunner’s glands negated this effect and depleted Lactobacillus (right).

This shows that mucin-secreting Brunner’s glands are important for promoting Lactobacillus growth.

Question: What directly controls Brunner’s glands?

Answer: The Vagus nerve that connects brain to gut and gut to brain.

Now, the Vagus nerve is involved in the “parasympathetic” (rest and digest) branch of the autonomic nervous system, in contrast to the sympathetic / fight of flight branch of the autonomic nervous system.

Thus, we start to form a picture whereby “calming” vagal parasympathetic “rest and digest” nervous system activity activates Brunner’s glands to increases mucin production from Brunner’s glands to feed Lactobacillus.

This is consequential because the microbiota in your intestines can directly (and through reciprocal activities on the nervous system) alter gut function and gut symptoms.

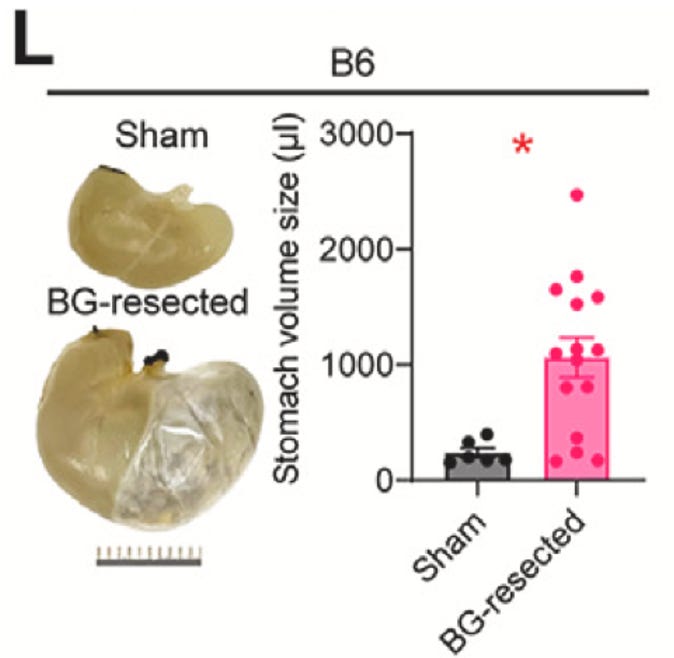

In fact, knocking out Brunner’s glands or the Vagus nerve connections to Brunner’s glands can lead to “severe gastric bloating” (as you can see below), as well as to “leaky gut” and heightened immunoreactivity.

And now, let’s complete the picture by adding in the master controller: the brain.

The researchers found one critical brain region was the central amygdala, which is the core of an almond-shaped brain center involved in emotions and stress response, was the master regulator.

Indeed, the researchers found activation of the central amygdala enhanced signaling through the Vagus and increased Brunner’s gland activity, to lead to an increase Lactobacilli and improved gut function.

In this way the central amygdala controls the microbiome.

And they showed that stress inhibits the central amygdala and lowers Lactobacillus levels.

Summary

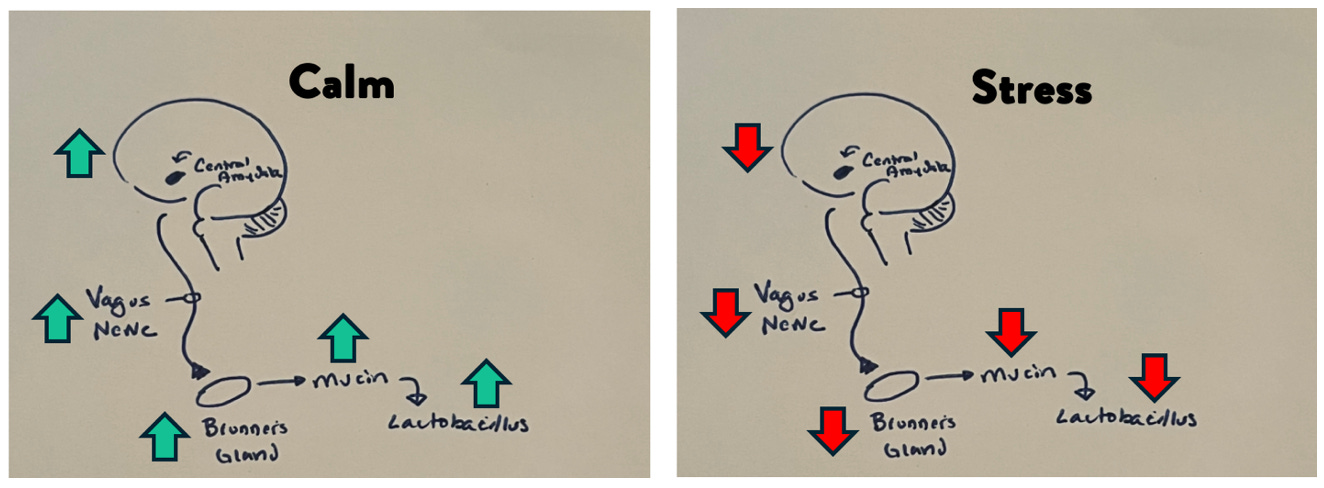

In summary these data are consistent with a model whereby the central amygdala signals through the Vagus nerve to increase secretions from Brunner’s glands which feed Lactobacilli, leading to better gut barrier function, autonomic tone, and less GI upset.

Conversely, stress decreases signaling from the central amygdala to Brunner’s glands, depleting Lactobacilli and leading to bloating and leaky gut, among other unfortunate effects.

Like my little doodle?

Nuance aside (feel free to skip): Really quickly, before getting into the actionables, astute viewers might have noticed that stress equates to LESS central amygdala activity, even though the amygdala is often talked about as the fight-or-flight region of the brain. This may seem counterintuitive. But – basically – brain regions are heterogenous with different neuron populations that carry out different jobs. So, don’t take this as a paradox, just a complexity. If that went over your head, ignore this last bit – but I did want to mention it for the uber-neuro-nerds out there.

Actionable Takeaways

What can you to do intervene on this pathway?

Well, perhaps the most actionable and inexpensive modality is through stress reduction exercises, including deep breathing, physiological sighs, yoga, meditations, or just doing whatever relaxes you.

On the physiological sigh front, this is a technique popularized by Andrew Huberman and involves a specific pattern of breathing, consisting of a double inhale followed by a long exhale.

On the user-specific relaxation technique, I want you to seriously contemplate what relaxes YOU.

Often, this falls into the category of “guilty pleasures.” And, if you’re anything like me and type AAA, you may even avoid these activities by virtue of the fact they aren’t productive. However, in sharing these data with you, I want you to contemplate that what might not seem productive may actually be productive in so far as it’s good for your gut health and metabolic health.

So, yes, that means, for me, I can rationalize curling up on the couch and binge-watching Game of Thrones or Marvel Movies as a “metabolically healthy” intervention.

What do you think of that?

Kinda’ a nice free pass to enjoy yourself, right?

In addition, consuming fermented food containing Lactobacillus may be beneficial: sauerkraut, kimchi; pickles; yogurt, Kefir

Let me know your thought and if this was helpful. And if you want the video version of the Newsletter, click on the video below.

Very interesting! Thanks for breaking it down (and the nuance aside is very helpful - I’ve only ever heard about the amygdala as the fear center of the brain).

Fantastic as always. What do you mean you are an AAA? What are the traits of this type of personality? What other measures do type AAA can use?