Do Dietary Guidelines Discriminate?

We review a new randomized controlled trial that suggests: current carbohydrate -skewed dietary guidelines may discriminate against certain racial groups. This is going to be a hard conversation.

If you prefer video to text, click below. Otherwise read on.

Do Carb-Heavy Dietary Guidelines Unintentionally Discriminate?

I’m going to ask you to bear with me on this one because I have some important and scientifically legitimate points to make, starting with a shocking statistic.

57% of Black Women have obesity. That’s substantially higher than the general population, or white women to 40%.

In fact, it’s no secret that – in general – rates of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases are higher in Black and non-White Hispanic populations in the United States as compared to whites.

Why?

There are some conventional answers, related to genetics, socioeconomic status, access to healthy food, and behavioral factors.

These have some legitimacy; however, they paint a discouraging picture that unmodifiable biological factors (e.g., genetics), or seemingly intractable social environmental and behavioral influences are perpetuating and exacerbating healthcare disparities.

Take an example, an 18-month 2015 randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of a “healthy eating” guidelines weight loss diet with 50% Calories from Carbs in White and African American women concluded that the African American women lost less weight because they had lower levels of physical activity; thus, explaining the health disparity with a behavioral characteristic.

New Randomized Controlled Trial

In the rest of this letter, I want to discuss a new human randomized trial, published in the Journal Obesity, as well as a commentary colleagues and I co-authored on the trial arguing for its tremendous importance with respect to fighting for a more metabolically nuanced and just future for nutrition.

More Background and “The” Question…

But before we get to the results of the randomized controlled trial, I want to arm you with more important background.

It’s already been documented that Black adults have greater insulin response to carbs and insulin resistance than non-Hispanic White adults, even after controlling for body weight and body fat distribution. Similar results have been found in Black vs white children.

Given that a larger insulin response in response to carbohydrate predisposes to storing fuel as fat and instigates increased hunger, decreased energy expenditure and obesity, we should ask…

The Question: “Could a reduced-carbohydrate diet, which stimulates less insulin secretion, particularly improve the effectiveness of weight loss dietary treatment in particular racial or ethnic groups with insulin dynamics that are mismatched to our current high-carb high-glycemic load diets?”

Main Study Findings: The Low-Carb Advantage

In this new randomized controlled trial, researchers randomly assigned 69 Black women with obesity to Low-fat (55% carb, 20% fat) and Low-carb (20% carb, 55% fat) weight-loss diets for 10 weeks with a subsequent weight maintenance period to examine energy expenditure.

They documented several interesting results:

Finding #1: Among participants with insulin resistance, there was substantially greater fat loss on the low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat diet (-4.9 kg vs -2.1 kg, p = 0.04). That’s twice as much fat loss on the low-carb diet.

Finding #2: Among participants with insulin resistance, total energy expenditure decreased substantially following weight loss on the low-fat diet but not on the low-carbohydrate diet (-230 kcal/day vs +67, p = 0.01).

Simply put, in black women with insulin resistance, the low-fat diet slowed metabolism with weight loss whereas the low-carb diet did not, or to a far lesser extent.

The implication here is that the lower carb diet provided a profound metabolic advantage with respect to maintaining weight loss.

Mechanism: Carbohydrate Insulin Model

Now let’s return to and reinforce the proposed mechanism at hand: According to the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity:

The rapid rise of blood glucose after a high-glycemic load meal (orange) raises insulin and raises the insulin-to-glucagon ratio (red) .

This hormonal response shifts fuel partitioning toward fat deposition (blue) , leaving fewer calories for the brain and other metabolically active organs.

And as a consequence, downstream of that, hunger increases or energy expenditure decreases (green) as compensatory mechanisms to reestablish an energy homeostasis.

Figure from Ludwig et al. AJCN. 2021

For individuals with a tendency to secrete large amounts of insulin, whether inherited or acquired, the carbohydrate insulin model predicts that a high-carbohydrate diet would exacerbate these events, leading to a vicious cycle of hyperinsulinemia, fat deposition, and hunger.

This is Where Conventional “Balanced Diets” Fail

Conventional behavioral weight loss targets (to “eat less” and “move more”) fail to address the metabolic drivers of obesity, making long-term weight loss maintenance unsustainable for many people, especially those populations with higher insulin secretion.

Now from this perspective, racial disparities in weight that might appear to be behavioral in origin – arising in the context of conventional guidelines that suggest consuming about half of Calories as carbohydrates – could instead arise from underlying biological differences with respect to insulin secretion.

Otherwise, and provocatively but reasonably stated, conventional advice around eating a one-size-fits-all MyPlate “balanced diet” might surreptitiously, metabolically disadvantage particular groups of people, including Black Americans and Black women, perpetuating healthcare disparities in obesity and obesity-related diseases that is often them blamed on behavioral factors, which perpetuates stigma.

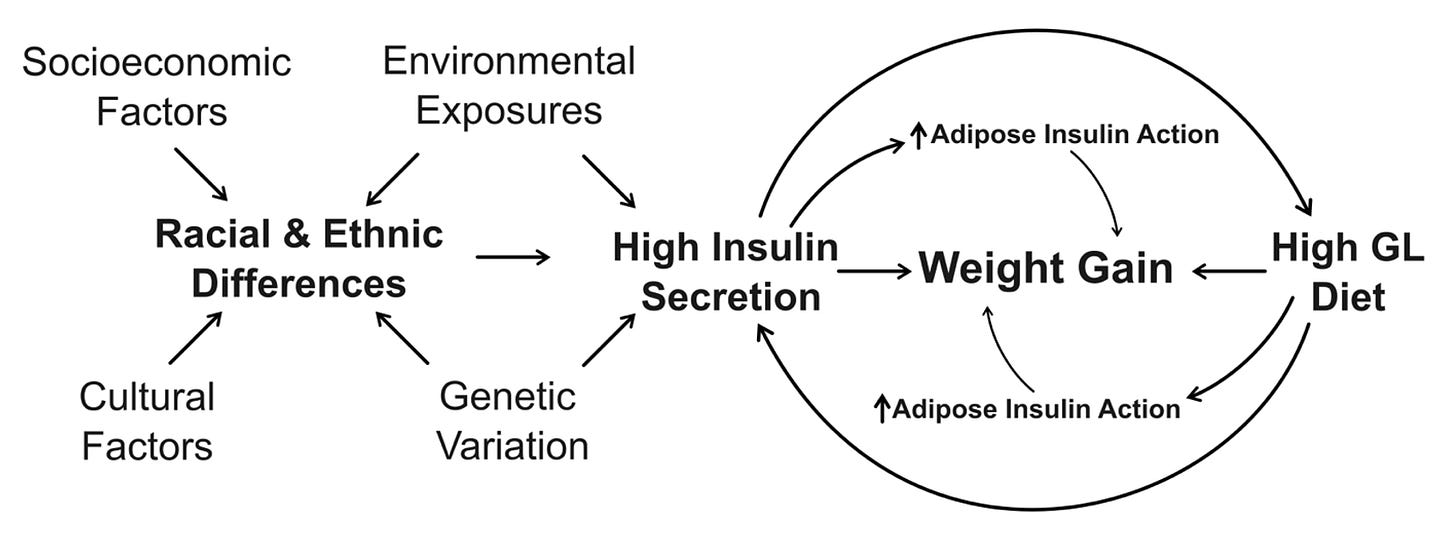

Additionally, I’ll highlight that other important factors, like socioeconomic and cultural factors, can also operate in the framework of this biological perspective – it can act as a convergence point and practical, productive framework to consider the how obesity develops.

Based on figure from Ludwig et al. Diabetes Care. 2022.

Thus, in addition to enhancing treatment efficacy of dietary interventions, this biologically oriented perspective may help close the healthcare disparity gap and lessen implicit stigma.

Conclusion

In closing, I just want to acknowledge these are not easy conversions to have, particularly because of the cultural dimension of diets. And to be clear, I am not saying certain racial or ethnic groups shouldn’t eat carbs or that carbs are “bad” per se.

In fact, race and ethnicity are relatively poor predictors of the underlying biological differences that matter, here insulin resistance and insulin response to carbs.

Nevertheless, we can still acknowledge that – for whatever upstream reasons, at a population scale – our current carb-heavy conventional may disadvantage certain racial and ethnic groups more than others and perpetuate stigma and disparity.

For more, please see commentary co-authored by myself and colleagues (Dr David Ludwig, Dr. Diana Thomas, and Dr. Cara Ebbeling). Click HERE.

Video:

this is a huge problem! we must address population specific metabolic network with different strategies and every one must have the possibility to access clear and honest informations about how to manage health and disease

I am with you in this new way of thinking

Not an easy topic to broach, but as usual, you do it with tact, grace, and DATA. 👍